From the ridge at the top of the mountain, the craggy landscaped stretched out below us. Cracked granite boulders were scattered around, protruding from the softer earth. A snaking switchback gravel road receded into the valley and the village below. Two hawks hovered motionless, as if levitating, scanning the ground for anything edible. The odd cloud floated by a few hundred metres overhead. On one side of the mountain range the ground was thrust up from the ground, rocky and harsh, on the other the landscape was completely flat, but for some depressions filled with water – the largest the Atatürk Dam which blocks the Euphrates. Our bleary eyes and tiredness were quickly forgotten thanks to the biting cold wind and, more importantly, the incredible 4:48am view.

Nemrut Dagi peak, with its plump grasshoppers, ancient statues, and the odd bird, is a surreal place to spend a sunrise. The other people there were wrapped in thick blankets, taking selfies with the sunrise and statues as light spread over the landscape. It’s humbling to think how many sunrises these statues have watched, and to wonder how many more they’ll watch after we’re gone. You can easily understand the appeal of creating a monument which will outlast your own life, that of your children, and even your empire.

As we descended in the new light, a commotion appeared around a bend in the gravel road. Carts, cars, and trucks were stopped haphazardly on the road and men were clustered in a small valley on the lower side of the road. As we drew nearer, the subject of the men’s attention came into view: a small Fiat resting on its side in the valley. Our driver murmured in horror – this was why his phone had been vibrating nonstop for the last half hour. His neighbour in the village had been descending the loose road with his two children in the pre-dawn light when he had apparently slid off the road and rolled into the ditch. None had survived.

The cries of veiled women pierced the morning air. One was slumped on the ridge of the valley in defeat. Somewhere out of sight, a man was sobbing. Our driver jumped out of the car and joined the other men with brief nods of acknowledgement. The three of us left in the car sat and watched the scene unfold in silence. A man was yelling into a telephone, a teenager ran for a car jack. More cars were stopping further down the road and hastily-dressed men were hurrying from them. I had half a mind to go down to see if I could help, but I was wary of causing offence – emotions were high – and I was in no rush to see any bodies. There was no shortage of villagers to help; I suspect I would have done more harm than good.

As we eventually drove away in another car, ambulances and men in fatigues holding rifles were speeding up to the site of the crash. Our driver – another man, the other was still by the wreck – said that there would be almost a thousand people there by the end of the day to see the bodies and pay their respects. Back down in the village proper, the car was swarmed by headscarfed women and a craggy-faced man with sunken eyes. They spoke rapidly with the driver in Turkish, expressions of panic flashing as the atmosphere turned funereal. He used us – ‘tourist’, the only word I could extract from the Turkish – as an excuse to extricate himself from the situation. I don’t blame him.

As you would expect, the morning’s events set a sombre tone for breakfast, locals talking in hushed voices as we tourists ate our post-dawn meal. It seemed cruelly ironic to couple such a beautiful sunrise with such a tragedy – in such a small town, too, the grief would be felt by everyone. The whole affair was an uncomfortable reminder how fragile life is – it could have been anyone, us included, that flew off that gravel road.

Back in Malatya, pushing the disturbing omen to the back of my mind, I caught a bus to the edge of town, found a suitable place, and stuck out my thumb. Grinning like an idiot – or was that just the sun glare? – I held my piece of paper on which was scrawled ‘KAYSERI’, a city some 350km away – the nearest major city to Cappadocia. I had been standing there for a grand total of seven minutes when a massive unladen truck screeched to a halt, the driver motioning for me to get in. I clambered up in to the spacious cab where I met my saviour, a friendly guy from Nevşehir, just past where I wanted to go.

On reflection, it was surprising just how disheartening even seven minutes of rejection had been; I didn’t expect to feel so put out watching just a few waves of traffic pass me with no reaction. I’m writing this from Izmir, about a week later, and thankfully that initial irrational disappointment does lessen – as long as you remember that it’s all in your head.

The guy who picked me up was Gökhan, a man who owned his own truck-driving business in Nevşehir. He spoke no English, but I got by well enough by using Google Translate to say things like “Turkey very beautiful” while pointing at the landscape. He said he had a cousin who was living in Australia – Brisbane – and there was one surreal moment where I was handed his phone to hear an Australian voice on the other end. He asked how I’d met Gökhan, I told him, and he responded “Of course! Classic Gökhan!”.

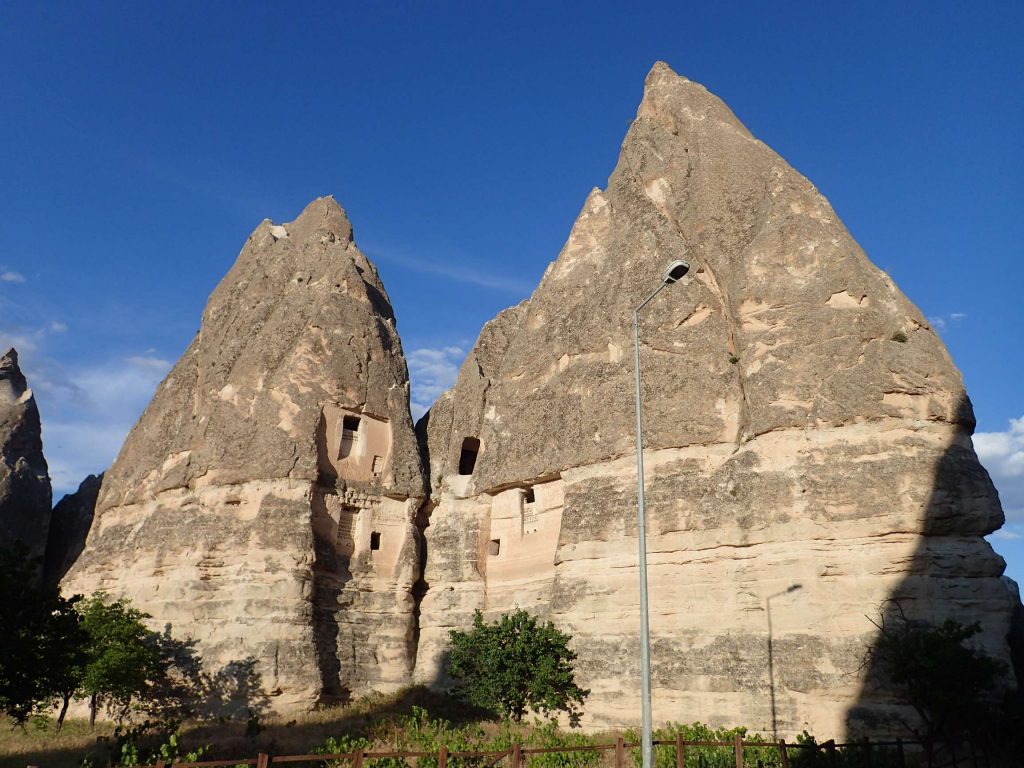

The landscape of Cappadocia is unlike anywhere else I’ve seen: miniature valleys carved from softer rock by water, wind, and time, large pillars standing clustered, ancient carvings, cave churches, and even underground cities. The whole region is formed by a mixture of erosion and human hands.

I had been recommended a hostel by some Europeans I’d met at Nemrut Dagi, it turned out to be a good choice. ‘Köse Pansiyon’ (…’cosy pension’) basically doubles as the owners’ house, and is one of Göreme’s oldest hostels at over 20 years. They have a wonderful dorm on the top floor with a great view over Göreme, good amenities, and decent WiFi. Also, it’s only 15TL (7AUD) per night.

Göreme is eerily deserted, especially for what is supposed to be peak tourist season. The odd couple could be seen wandering the roads, peering into barren restaurants. The street cats peer sleepily at you.

I got talking to a few of the locals – the human ones – and apparently this time last year the streets were clogged with tour buses and internationals, hotels and hostels alike full to the brim. This is one area where the effects of the recent terror attacks in Turkey can be strongly felt. Even Turks were refraining from eating before sundown, contributing to the anemic atmosphere. I wondered when I would get far enough west that the locals would be eating during the day. I found a cheap chicken kebab for dinner and had an early night.

The next day was lost to lethargy and general laziness. I managed to catch the sunset and go for walk around Göreme.

The next day I decided I should probably do something, so I headed to Uchisar. I ended up taking a wrong turn and the long way, apparently, as I found myself on a dirt road surrounded by fields. Despite the plumes of sand I kicked up as I walked, the land around me was teeming with life. At this time of year, one of the first things you notice about Cappadocia are the wildflowers. They are stunning in their sheer variety and abundance; I didn’t think hayfever affected me, but there is apparently a point at which pollen clogs all lungs. It was like walking through a painting, with blossoms of reds and orange-blacks mingling amongst soft white bristles, yellow stalks, and deep purple petals. The smell was extraordinary; they ranged from intensely sweet tiny white flowers that would make a good cordial – I later realised these were elderflowers – to musky, earthy purples and greens. I would have appreciated the scents for longer but I was spurred on by streaming nose and watering eyes. The chest-high wheat fields bobbed in the wind as their seeds wormed their way into my boots, while somewhere, always somewhere, a thousand crickets and small birds and insects chirped and buzzed and sang.

A surprising majority of the crops around Cappadocia are grapes for wine – apparently Cappadocian wines are world famous… the first I’ve heard of it. It’s probably more that the sandy land is most suited for hardy vines.

I made my way to the citadel peak and sat there for a good while, admiring the view:

I headed back to Göreme and booked a hot air balloon flight for the next morning. I paid 90 Euros – 300 lira – a steal, considering prices are normally around 160 Euros this time of year. Prices here are often in EUR, a measure of how tourist-oriented this place usually is. I was told to be outside my hostel at 4:15am. Yay.

I was up in time – sleep-deprived, but up in time nonetheless. A van came around, right on time, and I was taken with about eight others to a ‘holding pen’ – the company’s headquarters (I was with ‘Atmosfer Balloons’). Admittedly, it was a very comfortable holding pen, with free biscuits, tea and coffee, et cetera. Some nibbled, most too tired to eat; one guy from Queensland having drunk a little too much the previous night and ran to the bathroom at the sight of the food. I knew better than to pass up a free meal, though. Before long we were all called back to the van and shuttled to our takeoff zone as the sun rose – still hidden behind the hills. We passed about twenty other balloons on the way there, many laden with 20 or 30 people stuffed in one jumbo basket. Cappadocian airspace (yes, that is a thing) has two waves for balloon launches – we were in the second. I think that ends up being better, because you have more photographs with other balloons in them and you get more of the sunlight on the land. Thankfully, we had much smaller baskets with only nine or ten people each.

Some words are exchanged between the ground team and the pilot – and then you’re off! The gas burner above you roars as it fills the balloon with hot air and you drift up into the air, untethered. We gained altitude quickly, coming level with the other balloons:

When the burner isn’t drowning out all other noise, the lack of noise is actually quite mesmerising: you just float through the air, the only sounds coming from your fellow basket-mates.

Below us, the grapevines receded into a green and brown checkerboard cut by farmers’ paths and the occasional paved road. Evidently, the pilot likes to show off: he brings you down, down into a valley and swings you past some rocky chimneys, almost close enough to reach out and hop on to.

At the end of the valley, the pilot holds down the gas lever and we again shoot up into the sky, higher this time – 850m, he says with a grin, higher than the 650m height limit.

Finally, after about 75 minutes, we begin our final descent to the waiting pickup teams. About two minutes before we reach the ground, however, as we pass a field of golden wheat, Queensland guy decides he needs to make what is inside him go outside and treats the balloon passengers and ground crew to a vomit waterfall. He grins sheepishly at us, and says he feels much better. Clearly practiced and coordinated, the team of six or so maneuvers the balloon as it descends right on to the pickup trailer – impressive.

On the ground, we have slices of cheap cake and champagne mixed with fruit juice. Overall, a great experience, to the point where I agree with the consensus that it’s a must-do when in Cappadocia. You can get a good aerial view of the landscape from the top of Uchisar citadel, but nothing compares to seeing the entire place from the air at dawn.

I was dropped back at the hostel at 8:30am. I had time to kill before my 9:30pm overnight bus to Pamukkale, so I went to check out a nearby underground city. At its peak it could house 20,000 in its 85m deep network of tunnels, rooms, and churches. It was daunting enough to explore the 10% available to visitors.

I meandered around Cappadocia for the rest of the day before getting some food and an embarrassingly Turkish haircut (think ‘perfectly uniform dome’ on the back third of my head). Before long, bus time came and I attempted to sleep as we rumbled our way through the dark towards Pamukkale.

‘Til next time

– Alex

One thought on “Day 56: Death and Balloons in rural Turkey”

Comments are closed.

Hello Alex,

Really enjoying your blog!

Come and visit us in Guildford if you get as far as the UK

Sara