We caught the marshrutka from Mestia to Zugdidi after a hurried breakfast at 8am. From there, we arrived in Batumi a couple of hours later, a seaside resort town on the Black Sea near the Turkish border. Called by some the ‘Las Vegas of Georgia’, Batumi is one of the strangest cities I’ve ever visited. It’s a peculiar mix of construction, French/European buildings, and seemingly unplanned ‘modern buildings’. You walk around the main streets and foreshore and just ask yourself: ‘why?’

Funded almost entirely by the various vices of man, its economy is mercilessly seasonal: only the occasional tourist could be spotted, equally bemused as us. The glittering casinos, inhabited by bored staff and the odd bleary Russian or Turk, offered hollow promises of wealth. The Soviet-era seaside ferris wheel creaked next to an odd enormous globe suspended about sixty metres in the air by seemingly permanent scaffolding – it’s the building on the right in the above pictures. Underneath it, a stage was being disassembled. As a passing local told us, Maroon 5 had played here last night, a big deal – the biggest of deals – to the extent that people attended despite not knowing or liking the music. There’s a seaside-style ferris wheel right next to these modern buildings, lending a jarring sense of change to Batumi. The magnetic allure of ‘The West’, from the EU to pop music, is strongly felt in Georgia.

We caught a cheap public bus to the Turkish border. The border crossing at Sarpi/Sarp (the Turks have a habit of removing an ‘i’ from the end of place names) was relatively painless, there we even a few duty free shop staffed by some bored-looking employees. Upon walking into Turkey, we produced a piece of paper and scrawled ‘ERZURUM’ on it – I knew my sharpie would come in handy. We stood right outside the border, where all the traffic from Georgia passed. A few security guards wandered past now and then, smirking – one motioned that it was too far. After seeing a bunch of minibuses (in Russia/Georgia ‘marshrutkas’, in Turkey ‘dolmuses’) heading to the nearest Turkish town, Hopa, we added that to our piece of paper. About fifteen minutes later, a man with a close-cropped haircut and pink polo shirt grinned at us and motioned to follow him.

He said he could take us to Hopa, where we would have a better chance of a ride to Erzurum. We got in his car – a new, clean car – when he said we were waiting three minutes for something. Three minutes later, we found out exactly what that was as three more Turkish guys piled in to the car (we were already three after meeting a guy from Manchester on the bus to Batumi), two in the back and one in the front. This was not a small car, but it was just a matter of fitting seven people in a five-seater vehicle. I had been sitting in the front passenger’s seat, but when Pink Polo tapped the little area between the front seats behind the gear stick I dutifully took my new throne, cheek pressed to the ceiling – something everyone found justifiably amusing. An auxiliary cord was plugged in to someone’s phone, Turkish Top 40 was turned on, and we were off. Travelling at a speed only legal in a developing country, we made it to Hopa with three new friends, who we fistbumped and high-fived enthusiastically before farewelling. Pink Polo motioned for us to get back in his car, and we – a bit puzzled – obliged. We pulled up to an apartment building where he said he owned a shop, then he disappeared inside for a few minutes. When he returned, he had something hot wrapped in newspaper (he had said ‘ekmek’, bread, before), three chocolate bars, and three coca-cola cans. When we got out our wallets he completely refused to accept any money, then he drove us a few kilometers down the highway to a good spot to hitch to Erzurum. What a welcome to Turkey.

Waiting by the side of the road with our Erzurum sign – Hopa now crossed out – we opened the newspaper to find not just bread, but ham, cheese, and tomato sandwiches in freshly baked bread. We couldn’t believe the generosity, especially considering it’s Ramadan at the moment, meaning most Turks don’t eat or drink at all between sunrise and sunset. Talk about hospitality… just crazy. Speaking of Ramadan, I hadn’t realized it was happening until a few days before entering Turkey, and it put a significant damper on the food part of my Turkish journey – though apparently not on the friendliness of the Turks.

About fifteen minutes later, after many waves, honks, and a couple of false starts, two men in a little white car stopped a hundred meters down the road. We didn’t think anything of it, but after a few minutes they reversed and said they were going all the way to Erzurum. That’s a good 300km – we all squeezed in the back three seats, bags on our laps, and settled in for a long journey. Our saviours were sports coaches for a high school in Istanbul, they had just been in Batumi for the Maroon 5 concert.

As we sat down to eat, some far-off mosque’s muezzin’s call echoed through the valley, completing the scene: barren, craggy hills spotted with shrubbery, a deserted highway silhouetted by imposing mountains in a rapidly fading light.

We arrived in Erzurum at 11pm, tired and ready for bed. The brothers felt the same way; they found a cheap hotel (just 20 lira, 10 AUD) and we all five slept like logs.

In the morning, the brothers had left early. My two friends were catching a train to Ankara, I was determined to head southwest through Cappadocia to the coast. If Erzurum had looked grim at 11pm by orange streetlight, it looked even worse at 9am under grey skies and drizzle. The squat, sharp-edged apartments sat amongst auto repair shops, grocers, hairdressers and mosques. It’s a transportation hub for the surrounding area; the highway runs right through the center. I get the feeling nobody who can avoid it really stays in Erzurum for very long.

Thoroughly discouraged from standing by the side of the road with my thumb out thanks to the pervasive drizzle, I bought a cheap bus ticket to Malatya, a town near Nemrut Dagi, apparently a ‘must-see’ archaeological site. I saw my friends off and got on the bus, eager to leave Erzurum behind.

Despite my personal dissatisfaction at paying for what could – and perhaps should – have been hitchhiked, I was very impressed by Turkish long-distance bus travel. Mine was a sleek Mercedes bus with large reclining seats, clean interior, and uniformed staff. There were 8-inch airplane-style screens in the back of the seats (unfortunately, everything was in Turkish), outlet power, and after sunset the staff came around with tea and snacks. It was more like economy class on Qantas – I suppose you get what you pay for. A stark contrast to the death-on-wheels-beeping-harbinger-of-doom that is the Cambodian bus network.

At sunset, the bus pulled into an unusually large petrol station. Attached to the main building was a large cafeteria-style hall, cooks preparing for some impending battle. We were the first bus to arrive, but even as I watched more were arriving. As the muezzin’s call sounded, signalling sunset, people streamed into the hall, and within a few minutes it was packed to the brim with muslims breaking their fast. A fascinating sight. Back on the bus, although comfortable, the promised six hour journey turned out to be eleven hours, meaning I arrived in the Malatya bus station at two in the morning. For the first time in the trip, I saw an opportunity to use my sleeping bag, so I found a quiet-looking area of concrete and had a surprisingly decent night’s sleep in the bus station.

In comparison to Erzurum, Malatya was a thriving metropolis. The muezzin once again sounded from the mosque just as I got off the bus to the town centre. Malatyans were going about their day, shopping at the market, the sky was bright and blue. Malatya’s claim to fame is its apricots, which are apparently world-famous. It also produces fantastic cherries.

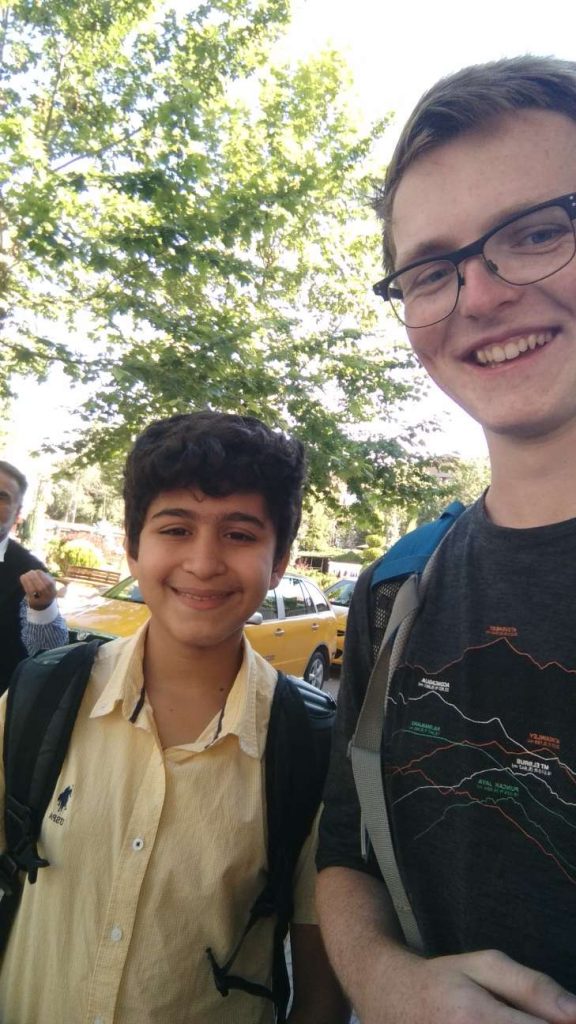

I was looking for the tourism office to work out how to get to Nemrut Dagi (some 80km away); some middle schoolers called out to me and I suddenly had my own personal army escorting me around Malatya. Hassling the local old guys, we eventually found the place, where they insisted we take selfies:

I found someone going to Nemrut Dagi in a few hours, so joined him and the five Taiwanese going with him. Meanwhile, I checked out the market.

I entered the market to buy some cheap bread and fruit (apricots, cherries) for lunch, and left with so much more than I bargained for.

Pide (pee-deh) is a variety of Turkish bread somewhere between a croissant and sausage roll pastry; I can’t place it exactly but it’s incredibly delicious either way.

Seeing me take a photo of the pide, the baker straight-up gave me one – again, like the first man with hitchhiked with, refusing to accept any money. There aren’t enough adjectives to describe how good that pide was. Wandering the market more, I picked out two tomatoes from an old vendor and held out a few lira, he also refused to take any money. What the hell? Is this normal? Turkey is making a fantastic impression so far; this is unbelievable.

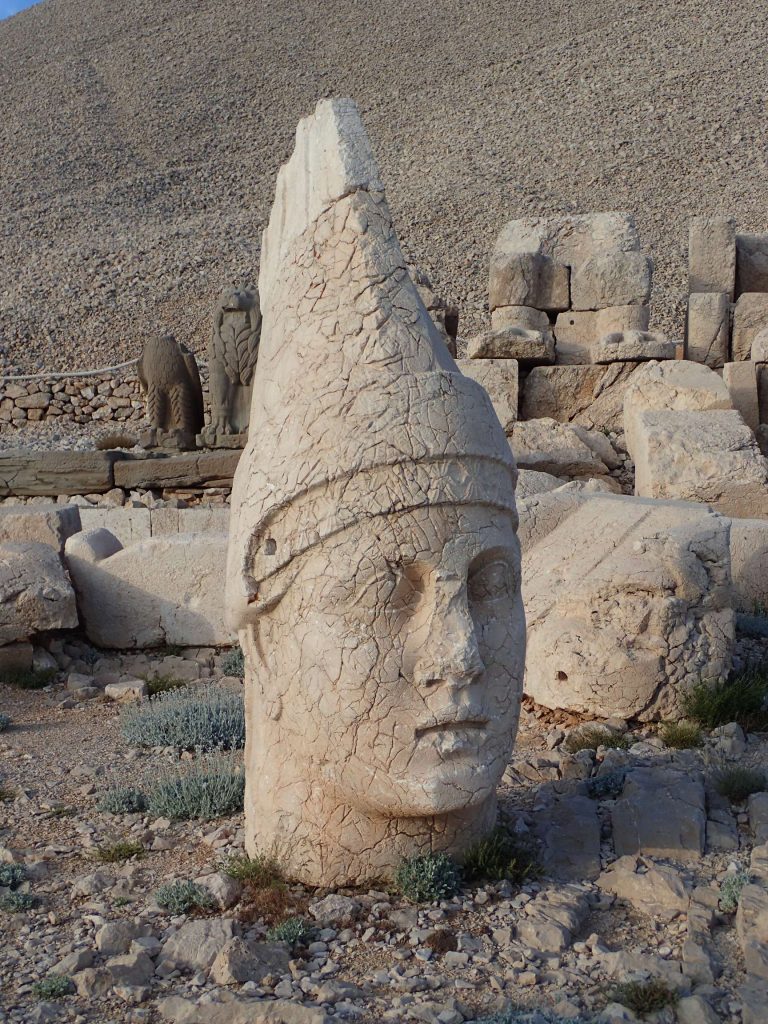

Before long we were driving up to reach Nemrut Dagi. Nemrut Dagi is a hilltop temple/tomb roughly in central Turkey, built by a megalomaniac king named Antiochus I about two thousand years ago. Although he ruled a relatively small empire – just a slice of central turkey – he build a monument to himself, his own seat next to those of the gods. Sitting on top of the region’s tallest mountain (2,150m), the view is truly impressive.

We crashed for the night in a place 12km from the peak, the promise of a pre-dawn wakeup call to catch the sunrise spurring us to sleep.

‘Til next time,

– Alex